The life of prayer and prayer itself must be considered under the light of the own vocation. We have read many times the affirmation of Fr. Karl Rahner saying the Christian of tomorrow will be a mystic, someone who has experienced something or will be nothing. Prayer is essential to the Christian life and, in a particular way, to this Christian way of life that we call religious life. That is why the first context of prayer is the vocation life. We must understand the vocation - the Christian life and religious life - as a relationship in which the Lord takes the initiative and we respond, thus creating an experience of the grace in which we are transformed into new creatures by the action of the Spirit in us.

Today we are witnessing a veritable explosion in the methods of prayer. Since the appearance of the book “Muéstrame tu rostro” (show me your face), by Ignacio Larrañaga to the present day, proposals for methods of prayer have not stopped appearing. Two of the most popular are the central prayer, the Trappist monk Thomas Keating, and the practice of meditation, the Claretian Paul D'ors. I mention these two in particular because both claim the origin of their identity in the great schools of primitive monasticism, and both have had a very special impact on many people, coming to create real movements whose identity lies in these practices of prayer.

But the methods of prayer are not new. If we look at the history of spirituality, we will see how in the sixteenth century and as an effect of modern devotion, we find proposals for prayer methods such as that of Fray Luis de Granada in his Book Of Prayer And Meditation, or as San Juan de Ávila, in his Audi Filia. Of much more scope and the impact was the one of San Ignacio in his Spiritual Exercises, concretely the contemplation to reach love. These modes of prayer also created schools, currents and spiritualities with an identity of their own that are currently valid within the framework of the experience of faith of many people. And it is that this seems to be the proper of a method of prayer: to create a school, a current, with a very own and determined identity.

Is there a method of prayer in the Order of Preachers? We would have to ask this question of Saint Dominic and the first friars of the Order. Both, Master Jordan of Saxony, the first biographer of Saint Dominic, and the rest of the authors of the primitive legends and the witnesses of the Process of canonization, tell us about the contemplative mood of Saint Dominic, highlighting his assiduity in the celebration of the Divine Office and in private prayer. The Constitutions of the Order in 1216 do not speak of a method of prayer in particular, except for the Divine Office and the secret prayer, which is what is known as a personal prayer in our Order. For the first brothers, the prayer was essentially liturgical, because it is the liturgy the context in which we contemplate the history of salvation that we also contemplate in the study and that we finally preach with and through the Word. Although the booklet on Prayer Modes of Saint Dominic shows us the variety in the forms and expressions of the prayer of Saint Dominic, perhaps we could not say that there we have a way of praying in Dominican.

Saint Teresa of Jesus defined prayer as a way of friendship being many times alone with whom we know loves us. Perhaps it is this affirmation that seriously poses the question: Is it necessary to have a method of prayer? The questioning can be deeper: Is there a method to get to establish a relationship of friendship? If we think of prayer as a living relationship with the Lord, prayer methods may be a stumbling block rather than a help. Sometimes it gives the feeling that many methods of prayer are so rigorous that the important thing seems to be the fulfillment of the method and not its very end, which is the relationship with God. But we can not lose sight of an unavoidable fact: the lability of human nature, which makes it worthy of a discipline, a method, a form, at least at the beginning of an experience. With the passage of time, with perseverance and discipline, the method is likely to fulfill its purpose: to live an experience of prayer in which the center is the relationship with God.

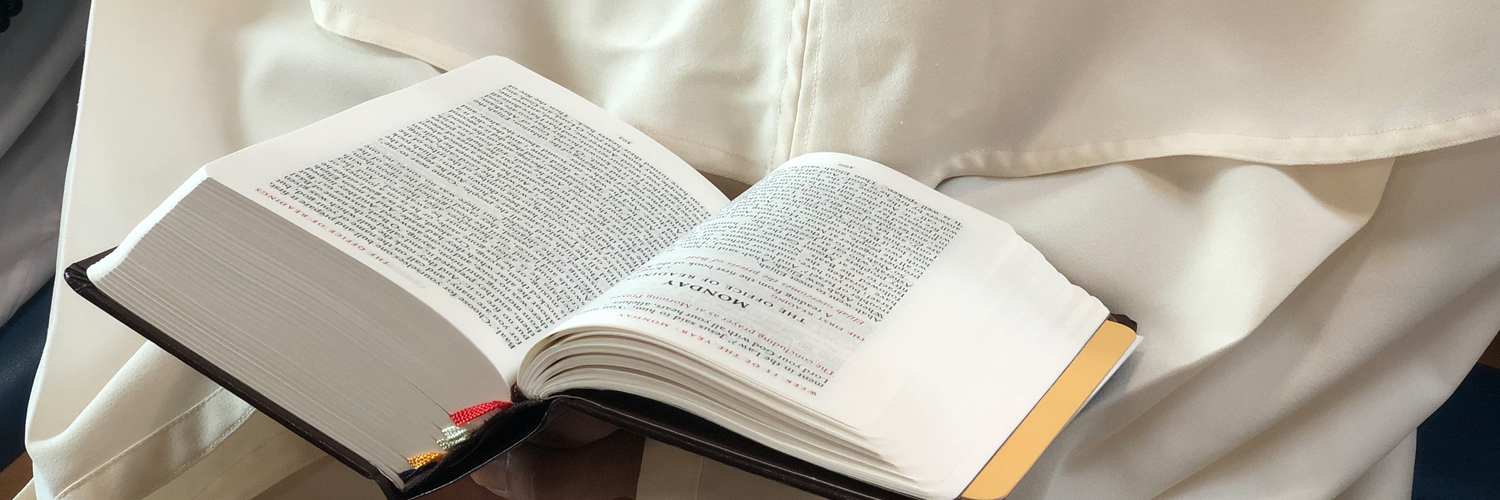

The Dominicans do not have a method of prayer that is our own, but I believe that the one that comes closest to our life and identity is that of Lectio Divina. Within the wide range of contemporary prayer, methods is that of Lectio Divina, although the expression is as old as Origen himself, who coined it. Much and very good has been written about this topic. Within the best that has been written, I dare to mention two specific documents: the book The reading of God. Approach to the Lectio Divina, by Fr. García Colombás, a Benedictine monk, and which includes the talks of some spiritual exercises that he once led to the Benedictines of Salamanca. And the other document is a Circular Letter that Dom Bernardo Olivera addressed to the entire Order on January 26, 1993, when he was Abbot General of the Trappists. Both documents offer not only a panoramic vision of the Lectio divina but offer truly intuitions valuable for those who wish to start in this exercise.

Within the popularization of Lectio Divina, there is, however, a problem: to enclose the Lectio Divina in a method that has its origin in the Scala claustralium, a letter that Guigo II the Carthusian wrote to his brother Gervasio. I think we all know that the steps of this scale are: lectio, metiditatio, oratio and contemplatio. Reading, meditation, prayer and contemplation. Some bolder, if not daring, have dared to add one more step: the action. The value of this document lies in the fact of showing us at the outset that the object of the divine reading is union with God. But already the

García Colombás himself warns the artificiality of every ladder and, therefore, of every method. The reading of God is so personal that each one must look for his own way. In any case, it is necessary to say that the steps of this staircase are not crossed one by one, but that the experience of traveling simultaneously can occur.

The important thing is to be clear in the practice of lectio divinathat its purpose is, in the words of Saint Gregory the Great, to read the heart of God. Since Sacred Scripture is a text inspired by God, the Bible is not for the Christian another book, a book of meditation or prayer. The Bible is a place of encounter with the Lord. This awareness allows us to discover that reading the Bible requires an approach to exegetical methods that reveal the true reality of what the authors wanted to convey to us. But that in all believing reading of the Bible the prayerful mood is essential, that is, a prayerful reading of the sacred text.

The identity of the Order of Preachers is given in his charism: preaching for the salvation of souls. This preaching culminates in the celebration of the sacraments of faith (Fundamental Constitution, VI) and implies a life that is realized in the living of a common life, in fidelity to the evangelical counsels up to the preaching itself, in the assiduity in the celebration of the mystery of salvation in the liturgy. (Fundamental Constitution, IV). From this view, we can say that if what gives meaning and identity to our life is the preaching of the Word of God, our prayer should be centered on the Word of God that comes to us through Scripture, Tradition and the signs of the times that demand of us clear answers from the faith and from the commitment of life.

Our life of prayer, as men and women of the Word, is called to focus on the Word:

- Word that we scrutinize in the study.

- Word that we welcome in silence, solitude and prayer.

- Word that we celebrate in the liturgy.

- Word that we proclaim in preaching and in committed witness of our daily life.

Finally, a suggestion about what text to read. In this sense, García Colombás and Bernardo Olivera differ. For the first, the lectio divinais, in a strict and exclusive sense of the word, a reading of the text of Sacred Scripture. For the second, on the other hand, the Lectio Divina gives the amplitude of reading the text of Sacred Scripture, the Holy Fathers and the Fathers of Cîteaux (we could change here by Dominican writers). In my personal opinion, the first vision seems more appropriate: the lectio divinais, essentially, a reading of the Word of God in the text of Sacred Scripture. But since Lectio Divina is an experience of personal relationship with God, it must have the necessary amplitude to encompass everything that allows us to relate freely and openly with the Lord. What we must agree on is one of the sentences of Bernardo Olivera: who says that everything is lectiodeclares that lectiois nothing.

The path can be:

- The Lectio with the liturgical texts of the day, that is, the readings of the Mass, the psalms of the Divine Office or the readings of the Office of reading, especially if they are those of the biennial lectionary, which do not coincide with those of the four volumes of the liturgy of the Hours, but with those of the monastic breviary.

- He read it with a reading followed by the Bible, from the beginning to the end, or through the historical, prophetic, sapiential and poetic books.

- The Lectio with a specific theme that is followed through the books of the Bible.

The important thing is that each of us is aware that we are called to be and we are men and women of the Word who have a place of encounter with the Lord in the Word of God.

Fr. Ángel Villasmil, OP